Rolando Vazquez Melken was a guest speaker in the fifth Writing for Transformation course and answered questions from participants about decolonial theory in the context of storytelling and journalism. He is Professor of Post/Decolonial Theories and Literatures, with a focus on the Global South at the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Rolando’s words are carried by me, Sanne Breimer. I have tried to listen carefully, and the following excerpts are based on my notes from the session.

The question of “who?”

How to apply the theory to professions outside of academia? A first thing to do, Rolando says, would be to locate the institution you’re working for geohistorically, along the lines of colonial history. Once you do that, you will see that its position isn’t neutral.

Rolando:

“In the structure of a university, for example, the colonial hierarchy with its dominant positionality in colonial order is reproduced. The people in the highest positions in Dutch universities are white and from a high class, and you will find the triangle of discrimination when you see the people doing the cooking and the cleaning.”

We need to begin with positioning ourselves and not replicate the same system we are fighting against; that consciousness is fundamental. The work of Catherine Walsh and Arturo Escobar about centering the question of “Who?” is recommended:

- Who is doing the work?

- For whom are you doing that work?

- With whom are you doing that work?

Once you apply these questions to journalism, you start to see that journalism shouldn’t be about people but with people. As a journalist, you should ask yourself what grants you the privilege to carry the voices of other people, and how is your story giving back to the community and not being extractive?

It’s about dignity, too. Decolonial theory is an ethical and political project; if you’re not working towards justice, you’re not doing decoloniality, Rolando emphasizes.

Even if you think your work is decolonial, it can still reinforce privilege and extraction, for example, in the context of art, when Western institutions exhibit work from the majority world for a predominantly white audience. You could apply this to journalism, too. Some of the organizations that do the real decolonial work don’t mention the word decolonial.

The role of the editor

The editor guarantees eligibility and formats. Academic texts are also for dissemination, and editors often edit out certain words that aren’t “normal” English. Decolonial academics push terms that the English language doesn’t know yet:

- Decoloniality vs decolonization. The term decoloniality isn’t just about decolonization; it’s a much broader concept (explained in a previous newsletter)

- Knowledges vs knowledge. Decolonial academics speak about the plural because they believe there isn’t such a thing as one dominant knowledge; there are several knowledges existing next to each other.

- Earthlessness and worldlessness as new words, expressing the loss of earth and worlds by colonial erasure.

Professor Vazquez Melken mentions how decolonial writers like Maria Lugones and Gloria Wekker had difficulties sharing their work because of the dominant language that doesn’t incorporate the nuances they were talking about. He talks about the concept of “coming to voice” as a decolonial process of undoing erasure. Colonialism has caused suppression and erasure of many other knowledges by implementing one dominant culture and knowledge.

Storytellers have a task of listening to bring back the cultural archives that have been silenced. Instead of doing research, which in its traditional form is also extraction, journalists should listen. If you listen, you are receiving, not representing.

From byline to carryline

As journalists, we don’t own the stories; we don’t become the author. When you listen, you receive and carry the story further. Decolonial storytelling is about challenging the dominant narrative and carrying critical perspectives without erasing the edges of storytelling. It’s about a critique of ecocide and eurocentrism, and implementing notions of ancestrality that the dominant narrative doesn’t recognize as truthful.

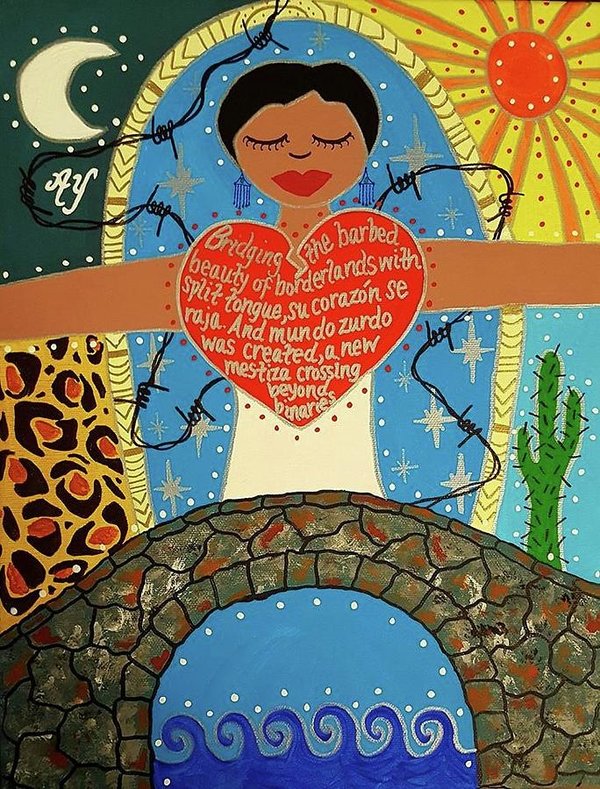

Storytellers can protect these narratives by receiving them and not dismissing them as inferior or exotic. Rolando points out that it’s a challenge and a long struggle to do so. How to listen to indigenous epistemologies that are not in text but in textiles and storytelling, for example? It means to challenge the validation of dominant structures, with English grammar that often erases characteristics. He mentions the essay How to Tame a Wild Tongue by Gloria Anzaldua. A short excerpt:

“So, if you want to really hurt me, talk badly about my language.

Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity – I am my language. Until I can take pride in my language, I cannot take pride in myself. Until I can accept as legitimate Chicano Texas Spanish, Tex-Mex, and all the other languages I speak, I cannot accept the legitimacy of myself. Until I am free to write bilingually and to switch codes without having always to translate, while I still have to speak English or Spanish when I would rather speak Spanglish, and as long as I have to accommodate the English speakers rather than having them accommodate me, my tongue will be illegitimate.

I will no longer be made to feel ashamed of existing. I will have my voice: Indian, Spanish, white. I will have my serpent’s tongue – my woman’s voice, my sexual voice, my poet’s voice. I will overcome the tradition of silence.”

Anzaldua writes in Chicano English, a dialect of American English spoken primarily by Mexican Americans (sometimes known as Chicanos), which enables her to think differently, Rolando explains. He says that no author from the center, from New York, Paris, or Germany can think what she is thinking. We need to listen to the voices of those who have been dismissed and dignify them.

From representation to reception

The privileged position is a narrow place, and to be in relation with others means humbling yourself. Native English speakers, for example, don’t assume a position of dominance but also don’t realize that non-native speakers have lost their ancestral or mother tongues and seek ways to express themselves through English. It’s an imperial language, but it also depends on how we use it. It makes you think about the grammar rules we apply rigorously, right? What if we shifted grammars and appreciated the space where mother tongues come through?

At the same time, in the context of the Netherlands, where the far-right leaning government wants to impose the Dutch language in universities, the English language becomes the space where interculturality happens and other archives can come into conversation.

The function of decolonial journalism is not extraction but giving voice and taking the knowledge of people seriously, acknowledging that people have knowledge. You don’t need to add your voice to explain the story; you just need to listen. People know their own situation best, any group of women in any community will know already what is happening, so why not take them as sources of knowledge instead of writing about their experiences?

Rolando makes an interesting point about the paradigm of representation, which is colonial, too. Instead of the power of narrating a story, we should move from representation to reception, and to do that is to learn how to listen. As a storyteller, you have the capacity to receive the lives of others and transmit them. You don’t create a narrative, you’re not representing others. Instead, it’s a process of honouring what others tell you and listening to what has been erased.

From one to multiple journalisms

One of the tasks of decoloniality is to humble yourself. Once you do that, you don’t want to take over anymore; you become “us” instead of “I,” and you will enable pluriformity to flourish. In storytelling, it means to let different realities and different truths exist next to each other. Instead of replicating the dominant narratives created by power and algorithm, you can use the dominant tools to ask yourself who you are honouring, who you are writing for, and what your stories mean to the people you write for.

These small questions, Rolando says, are the most powerful. If you’re a science journalist, for example, implementing decolonial theory in your work is not about questioning science that says two plus two equals four; it’s about the fact that global science isn’t geared towards healing the earth, it’s geared towards capitalism. The practice of decolonial journalism in this context is about the financing of science and the interest behind it, and the fact that it’s white patriarchal science.

You will start to see the modern colonial structure of science as supporting extraction. The more you heal the earth, the more human you are. The same applies to health: what is health, what is the idea of health, and when did the body emerge as a machine? When did we start being repaired or segmented? For some people, this approach to the body as an apparatus is violent and conflicting with their culture and beliefs. It’s not just about access to health services; it’s also about the notion of bodies and healing. Questions like that are fundamental to ask yourself when practicing decolonial journalism.

Sign up for the waitinglist for the next Writing for Transformation course or subscribe to The Inclusive Journalism Weekly newsletter.

You must be logged in to post a comment.